Nuclear waste is presently a fundamentally hard issue that must be overcome before nuclear energy becomes sustainably viable. The issue with current nuclear reactors is that they allow the build-up of heavy radioactive waste, which has incredibly long half-lives and will produce toxic radiation for millennia. This issue is currently being combatted by disposing the waste deep underground to prevent environmental leaks, and through mitigating the radioactivity of waste. However, there have been some promising proposals to this issue, such as using fast breeder reactors that can break down heavy radioactive waste into harmful and short-lived waste. Proposals like this are still mostly theoretical, and studies into them do not indicate whether they are still feasible.

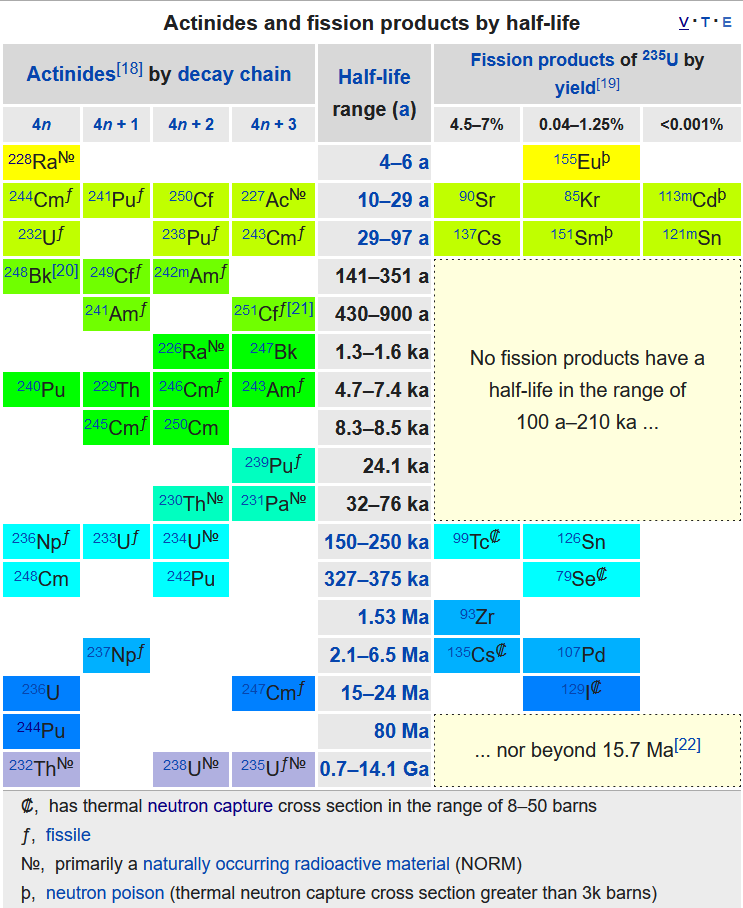

Radioactive waste is measured based on the substance's half-life and its radioactivity: (according to the International Atomic Energy Agency)

The majority of all nuclear waste is considered LLW or lower, and takes up approximately 90% of the total volume of nuclear waste, while producing mere fractions of the total radiation released by nuclear waste.

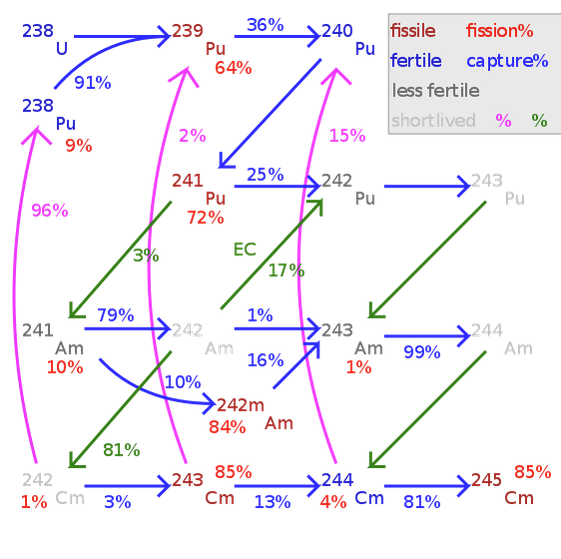

Standard nuclear fuel cycles end up producing transuranic waste products, i,e. isotopes with a greater charge than Uranium, and minor actinides, elements created via chains of neutron capture.

In chains of neutron capture, neutrons are absorbed by large radioisotopes such as Uranium-238, allowing numerous instances of $\beta -$ decay and the production of heavy actinides. These isotopes take much longer to decay into harmless materials when compared to other radioisotopes, for example while Radium-228 has a half-life of 5.75 years before $\beta -$ decay, Plutonium-244 has a half life of 80 million years before it undergoes $\alpha$ decay.

While HLW account for less than 0.1% of the total volume of nuclear waste, it is the most dangerous in terms of radioactivity, and due to this it has posed incredibly hard to effectively store, considering the quantity of HLW increases by 12000 tonnes every year. Estimates show that it accounts for 95% of all the radiation produces by nuclear waste.

Nuclear waste, specifically ILW and HLW, pose significant threats to the environment, if improperly stored. The high levels of radiation released by leaks of nuclear waste can cause cancerous growth in animal and plant life, and cause significant genetic changes that may affect generations of life.

Human exposure to HLW and ILW results in severe radiation health effects, such as:

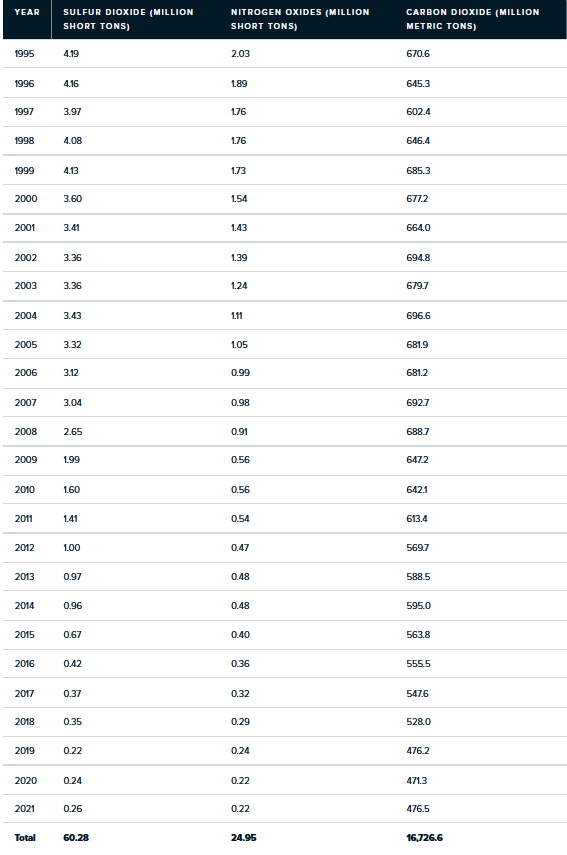

Compared to coal and gas combustion, nuclear energy produces radioactive toxic waste, whereas coal and gas produces greenhouse gasses (GHGs) which unhelpfully amplify the Greenhouse effect.

Studies conducted by the Nuclear Energy Initiative show that the United States alone has avoided producing almost 17,000 million tonnes of Carbon dioxide emissions. This is by discontinuing coal and gas power plants in favour of nuclear power plants, which produce significantly less carbon dioxide or GHG emissions.

Furthermore, there is an estimated 250 million tonnes of nuclear waste in storage. In comparison, over a billion tonnes of coal alone is burned for energy, producing approximately 2.86 billion tonnes of purely carbon dioxide emissions. Although nuclear waste is highly toxic to organic life and is a financial burden to store safely, compared to the harmful by-products of coal and gas combustion it has less of a negative impact on the environment. Coal combustion alone contributes the most carbon dioxide emissions when compared to all other sources of energy, and has significantly amplified the effects of the Greenhouse effect.

Thus, compared to coal and gas combustion, nuclear waste is much more ecofriendly in terms of its contribution to the Greenhouse effect.

Scientists in recently years have tried to mitigate the toxic properties of nuclear waste by treating waste to be more easily stored. This is initially done through vitrification, the process by which nuclear waste is stabilized so that it does not spontaneously react or decay for long periods of time. Numerous other methods of remediation have been considered, such as bio-mediation, as specific biological organisms have shown to be adept at decomposing certain radioactive wastes such as Strontium-90.

It should be noted that not all nuclear waste has no applications in the real world, and some waste isotopes such as caesium-137 have been used for food irradiation.

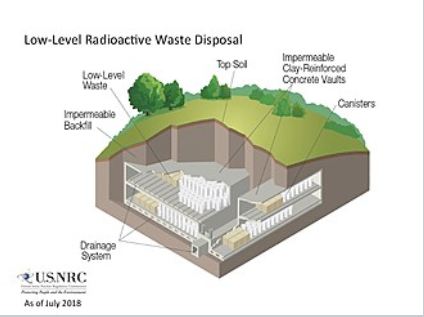

Currently, geological means of storing the waste has been favoured, as it keeps the waste far away from contaminating ecosystems. In general, large, stable geological sites are dug out via either mining equipment or tunnel bores, where waste will be kept. The core idea is that nuclear waste is kept far away from any human activity. Generally, extra security is kept around nuclear waste, such as concrete walls.

This method has not proven to be fully effective, as there have been numerous instances where nuclear waste has leaked from its containment, into local environments.

There have been recent developments in using transmutation, i.e. creating nuclear reactors to transmute nuclear waste into shorter-lived and potentially less dangerous nuclear waste. However, these forms of experimental nuclear reactors most likely will consume more energy than they produce, which makes them financially unsustainable.

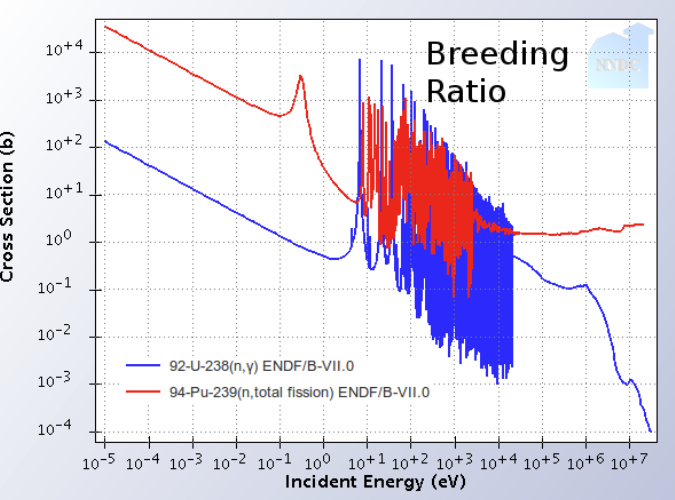

The idea of fast neutron reactors have been thrown around as a viable new type of reactor that solves the issue of nuclear waste. Presently, thermal nuclear reactors are used, where neutrons move at almost exactly the same speed as the nuclear fuel inside the reactor. However, fast neutron reactors are when there is no moderation or slowing-down of neutrons, and instead move at significantly faster velocities.

In thermal reactors, neutrons move at about 2200m/s, while in fast neutron reactors, neutrons move at more than 9 million m/s.

The significantly increased speed of neutrons significantly reduces the capture to fission ratio. When a neutron collides with an atom, it can either be absorbed by the atom's nucleus, or cause nuclear fission, which is the fundamental principle of nuclear energy. According to de Broglie's Wavelength Hypothesis, all matter exhibits wave-like properties, including neutrons. Faster neutrons have a larger amplitude and a shorter wavelength, as they have a greater kinetic energy. Thus, when faster neutrons collide with the atoms of nuclear fuel, they spend less time inside the nucleus, and thus are less likely to be absorbed, Furthermore, the intense energy of the neutron increases the chances for fission to occur, as the impact force favours nuclear fission.

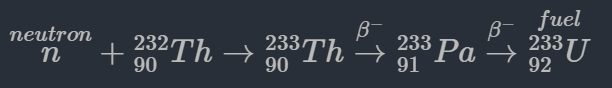

With models of fast reactors, breeder reactors become even more viable, which stipulates that a high neutron economy can be managed via fission reactions that produce more neutrons than required to initiate them. In this way, fuel is 'bred', by using these neutrons to convert fertile fuel into fissile fuel. Fertile refers to material that is itself not fissile, but can be converted into fissile material via neutron absorption. For example, when fertile Thorium-232 absorbs a neutron, it undergoes 2 reactions of $\beta -$ decay to produce fissile Uranium-233.

In thermal breeder reactors, this process produces unsustainable, heavy transuranic elements, which compose the majority of HLW and are a major downside to thermal breeder reactors. However, due to the immense speed of neutrons in fast breeder reactors, even the largest and longest-lived nuclear waste can undergo nuclear fission. In doing so, fast breeders can convert HLW into harmless waste that would decay much faster.

There are some downsides to fast breeder reactors, however. Currently, the process is entirely experimental, and current data shows that the concept of a breeder reactor may not be feasibly possible in the first place. Experiments have only achieved a neutron to fission ratio of 1.1, which while would sustain a fast breeder reactor, does not allow random loss of neutrons. Furthermore, currently models for fast breeder reactors incur some consequence in their upkeep, for example Thorium-based fast breeder reactors build up Uranium-232 waste, which generally will produce a wide array of radioactive waste. Furthermore, Protactinium-231 is an intermediary atom in the production of fissile Uranium-233, but eventually as concentrations of Thorium-230 decrease, the amount of Protactinium-231 becomes equal with the amount of Protactinium-231 that undergoes neutron absorption, resulting in a significant loss of efficiency and energy produced.

Furthermore, investment into this new concept of nuclear energy is expensive, as fast breeder reactors demand extreme environments and exotic coolants. The need for exotic coolants stems from the idea of elastic collisions, as neutrons that collide with heavy compounds lose minimal amount of energy compared to neutrons that collide with smaller compounds, such as water. Exotic coolants must be cared for and tend to react with materials of the fast breeder reactor, and thus even more money must be expended to sustain the use of these coolants.

The possibility of liquid metal, or molten salt as mobile phases for transporting nuclear fuel is a promising concept. For example, the BN-600 reactor in Russia uses melted Sodium as its mobile phase. However, Sodium reacts vigorously with standard environments, and there have been numerous instances of fires in the reactor as a result of the Sodium coolant. Furthermore, it appears that the technology and engineering behind fast breeder reactors is simply not advanced enough to accommodate for both the extreme environments and the use of experimental coolants and mobile phases. Molten salt is also viable, however due to the nature of ions, some cations may oxidize and produce insoluble salts that could cause unpredictable damage to the internals of fast breeder reactors. For example, salt containing Chlorine have chloride ions that may absorb neutrons such as when Chlorine-35 becomes Chlorine-36, which beta decays into Sulfur-36. There has been promising study into the use of $FLiBe$ mixtures, i.e molten salt of Fluorine, Lithium and Beryllium.