Democritus (460 - 370 BCE) describes matter as infinitely divisible and proposes matter is made up for tiny indivisible particles, with nothing between them but empty space. He names these particles “Atomos”, which means “uncuttable or indivisible” in Greek.

The term “element” is coined by Robert Boyle’s The Sceptical Chymist. Boyle defined an element as a substance that could not decompose into other substances. (Essentially indivisible).

Law of conservation of mass: Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier conducts numerous experiments, such as heating tin to form ‘calxes’ (metal oxides). Lavoisier pioneered the use of precise numerical measurements, and concluded that there was no change in mass during a chemical reaction.

John Dalton:

(1803-1808)

John Dalton came up with a theory of atomic matter:

NOTE: Following a modern understanding of atomic structure, Points 1-2 and 5 are incorrect. Atoms can be divided into subatomic particles, Atoms of the same element may have different masses (isotopes), and elements do not always combine in the simplest whole-number ratios. (e.g. sucrose ($C_{11}H_{22}0_{11}$))

The law of definite proportions:

Dalton proposed: “compounds are formed when atoms of more than one element combine in a specific ratio.” This is true given our modern understanding of chemistry, as Calcium oxide, for example, will occur with Ca and O atoms in some fixed ratio

The law of conservation of mass:

Dalton proposed: “atoms are not created nor destroyed or changed into different types; a chemical reaction involves separation, combination or rearrangement of atoms.” Thus, there must be the same amount of atoms in the reactants of a chemical reaction as the atoms in the product.

The law of multiple proportions:

Dalton proposed: “Whenever two elements form more than one compound, the different masses of one element that combines with a fixed mass of the other element is always a whole number ratio.” 95% sure this is wrong

Why is Dalton wrong?

He had a rule of ‘greatest simplicity’, which made some of his calculations incorrect. He assumed water was HO, and ammonia NH. Because of this, his measurements for the weight of oxygen was wrong by half of its actual value. Similarly, he made no suggestions for the structure of the atom.

Why is Dalton right?

He identified elements as consisting of indestructible particles called atoms. Good on him, but his calculations were bad

Dimitri Mendeleev:

(1868-71)

Mendeleev is credited with being the first to describe elements within a 'table', and represent this table according to patterns and properties he identified.

He published a book called Osnovy khimii, or The Principles of Chemistry. In this book, he established that orderings of atomic weights could be used to create groupings.

His goal was to create an ordered system to break down and make sense of the chemical/properties of elements known at the time, which were disjointed and confusing.

Going on, he would state that "elements arranged accordingly to the value of their atomic weights presents a clear periodicity of properties". This is where the “period” in “periodic table” comes from. Essentially, he correlated atomic weight to valency.

He could correlate valency as John Newlands had discovered the Law of Octaves, stating that every 8th element has similar behaviours to one another.

Based on his calculations, Mendeleev created an elaborate table, with spots for undiscovered elements and even suggestions for the correct values of atomic weight of certain elements.

This table would be validated due to the discovery of gallium, scandium, and germanium (1875-1886), which fit into Mendeleev's periodic table.

J.J. Thomson:

(1897)

J.J Thomson would pick up the work of Michael Faraday, who discovered the electrical properties of atoms. Working alongside other scientists (Julius Plucker, Sir William Crookes), he developed the cathode ray.

Essentially, a cathode (negative terminal) would release these rays towards the anode within a partially evacuated glass tube (cathode ray tube(CRT)). Cathode rays would cause gasses to glow like Neon in a sign. They found that a cathode ray can be affected by other negative/positive plates, and by a magnetic field.

Thomson stated that the material of the cathode did not affect the cathode rays. He assumed that they were not a form of radiation but negatively charged particles with some mass. These particles were electrons, which is why Thomson is credited with their discovery.

Thomson used both properties of cathode rays, being that they are deflected by both magnetic fields and charged metal plates, to adjust the strengths of both tools so the cathode rays would be unaffected. This would allow Thomson to determine the charge to mass ratio ($q_e/m_e$) for the cathode ray particles (electrons). The ratio he determined was about $1.76 \times 10^{-8}$ coulombs per gram. Knowing the charge to mass ratio of aqueous ions, Thomson estimated the mass of an electron to be less than a thousandth the mass of the lightest atom, Hydrogen.

This proved that atoms must be divisible.

Later on, Robert Millikan used Thomson’s charge to mass ratio to find the mass of an atom, $9.11 \times 10^{-31}$ kg, which is 1/1800 of the mass of a hydrogen atom.

Thomson’s model of the atom was pretty weird.

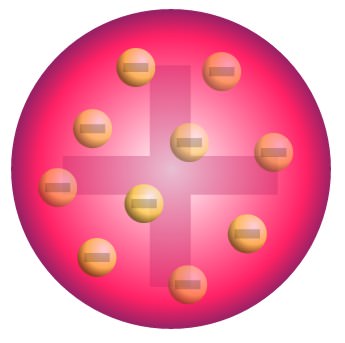

At that time, it was known that matter was made up of atoms, which was electrically neutral.

It was also known that there were negatively charged particle known as electrons, with a very small fraction of the size of an actual atom.

So, Thomson proposed the plum pudding model, where negatively charged electrons were embedded within a larger uniformly positively charged sphere, like plums in plum pudding. This sphere would account for the majority of an atom’s mass.

Other stuff: (1906) Thomson used positive rays to discover Neon in 2 different types of atoms (its charge/mass ratio was different). Thus, he discovered isotopes in a stable element.

Ernest Rutherford:

(1911)

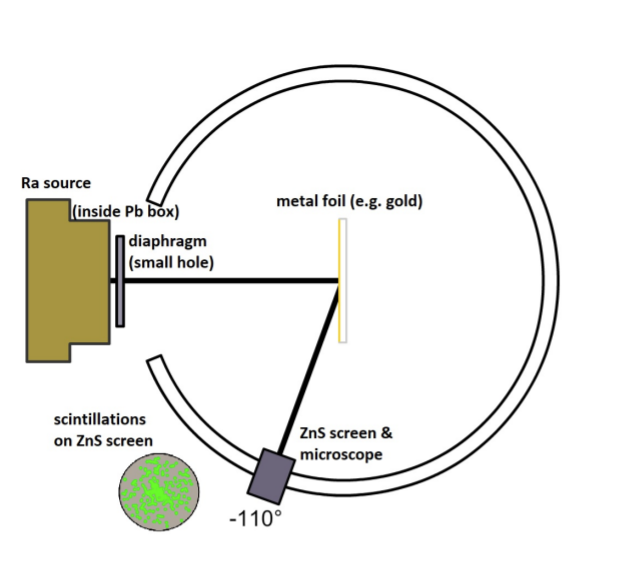

Rutherford, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, use alpha particles (2+ charged helium nuclei, literally helium without its electrons) on gold foil.

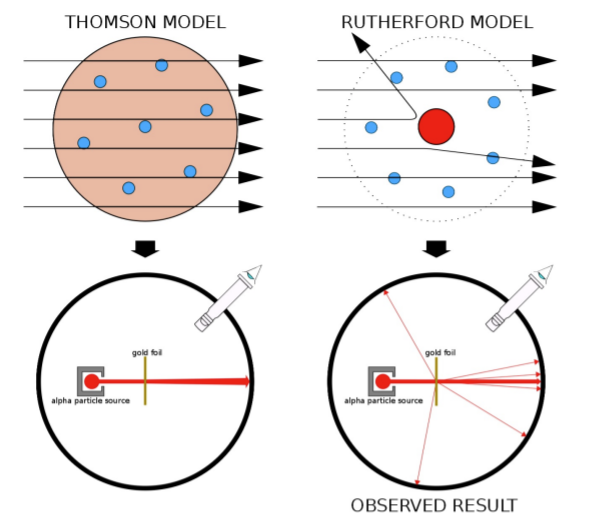

Assuming Thomson’s model was correct, positively charged alpha particles would pass through the gold foil with little or no deflection, because the positive charge/mass would be thinly and uniformly spread out across the atom.

In the gold foil experiment, a beam of alpha particles (+2 charged helium nuclei without electrons) were emitted from a radioactive material (radium), where they would hit a thin gold foil.

When the beam interacted with the gold foil, flashes of light could be detected using a microscope, as a result of the alpha particles hitting a Zinc Sulphide screen surrounding the gold foil.

The Gold foil experiment found that most alpha-particles incurred no deflection, however some alpha particles were greatly deflected, even back into their own direction.

Simply put, Thomson's model could not explain the results of the gold foil experiment.

Thus, Thomson’s model was disproven, as the deflection suggested a variance in the mass of an atom, with the majority of mass being concentrated in an area.

Rutherford proposed a new model, with an atom consisting of mostly empty space occupied by electrons, which orbited a tiny central region known as a nucleus. In this model, all positive charge is in the nucleus and all negative charge is found in the electrons. This explains why the alpha particles were so greatly deflected, as although most particles passed through the empty space, some particles would go close or impact the dense and positively charged nucleus, which would deflect them.

Niels Bohr:

(1913)

Rutherford’s model also did not account for emissions spectra (aka line spectra). Low pressure gasses and vaporised elements would produce these spectra when excited by electricity.

Similarly, based on classical physics, an electron constantly moving around would cause it to radiate energy, losing its energy and speed as it is pulled into the nucleus. This would mean all atoms are unstable, which is wrong.

Niels Bohr applied quantum theory to solve this problem with unstable electron orbits and accounted for the emissions spectra.

He proposed that electrons moved around the nucleus in circular orbits, however there were only specific orbital radii. He also assumed that an electron in an orbit would have a specific amount (quanta) of energy, where the closest orbital to the nucleus would have the least amount of energy.

He also hypothesised that a photon would be emitted from an excited electron, which was an electron not at its ground state, which is the lowest possible electron quantum level (energy states), as it fell to a lower energy orbit. NOTE: The energy of the photon is equal to the difference in energy between the 2 orbits. The frequency of the photon could be determined using the formula $E_{photon} = hf$, where $h$ = $6.626\times10^{-34}$ and $f$ = frequency. However, Bohr went against classical physics by proposing that electrons would orbit a nucleus without losing energy.

Thus, Bohr determined the energy associated with each of the electron energy states of the hydrogen atom. Using this, Bohr could calculate the wavelengths of light that corresponded to the emissions spectra of hydrogen. He was pretty correct. Good job.

Bohr’s model accurately described emissions spectra. Similarly, it explained the formation of absorption spectra, as electrons would only allow photons of a specific energy that corresponded to the difference between the energy state it would move to and its current one to excite them. The electrons would absorb the photons, but not the ones that weren’t the right energy. This created the absorption spectra, which outlined the wavelengths of visible light that were absorbed.

Bohr’s model describes the electron’s smallest orbit corresponds to its lowest energy state, which he called the ground state. Because of this, Bohr established atomic stability, as the electrons won’t crash into the nucleus given they cant go below the ground state, which will always be a positive radius from the nucleus.

Henry Moseley:

(1920s)

Before Moseley, it was believed that atomic number was continuous and was loosely defined. Essentially, Moseley used experiments to prove that atomic numbers could be rationalised from the physical state of an atom's X-ray spectra.

Francis William Aston:

(1920)

Having considered the possibility of isotopes, Aston set out to find a way to analyse and detect isotopes.

He would pioneer mass spectrometry (an analytical technique used to measure the mass to charge ratio of an element's ions.)

Using his own mass spectrometer, Aston identified the isotopes of Neon, Chlorine, and Mercury. He also wrote books, Isotopes and Mass-spectra and Isotopes.

Jean Baptiste Perrin:

(1926)

Perrin's contribution derived from Albert Einstein's paper titled "Investigations on the Theory of the Brownian Movement", discussing the idea that particles suspended in a fluid moved random due to collision with other atoms.

He studied 'colloids', which is a mixture consisting of an insoluble yet microscopically dispersed substance suspended within another substance.

In essence, while Einstein did all the math for Brownian motion, Perrin used experimental data to prove the validity of Brownian motion. Furthermore, he proved that colloids obey the gas laws.

You don't need to know about the gas laws, but if you're interested heres a website: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Physical_Properties_of_Matter/States_of_Matter/Properties_of_Gases/Gas_Laws/Gas_Laws%3A_Overview

He could then use that knowledge to calculate Avogadro's Number, or the number of molecules per grammolecule (gram/relative atomic mass) of a gas.

Erwin Schrödinger:

(1926 - Early 20s)

Bohr’s model had some issues, because there was no reason for electron orbits to be quantised, and no reason for “atomic stability” (wow lucarelli, very descriptive, it essentially asks why the ground state orbit was the lowest energy state for the electron(ground state = $E_1$)). Also, it could not successfully predict the emissions spectrum of atoms that had more than one electron. (It could only predict emissions spectrum for $H$, $He^+$, $Li^{2+}$, etc.)

(1924)

During the early 20s, **Louis de Broglie** proposed that electrons could have a wave and particle nature, much like light acting like a particle and a wave.

This wave nature would explain the discrete (quantised) energy states.

Because of this, Schrödinger and Werner Heisenberg developed a new quantum mechanical theory for the electronic structure of the atom, the Wave mechanical model.

In their model of the atom, electrons do not orbit the nucleus, instead Schrödinger treated them as mathematical waves. Schrödinger’s model is purely based on quantum ideas. Electrons had a probability of being found at a certain position. In this model, electrons don’t have specific path, but a probability of being in a location at a specific time. (sounds a lot like quantum physics because it is :)) Rather than neat, clean orbitals, Schrödinger’s model proposed electrons inhabited a “cloud”, and where the cloud is most dense is the most likely place to find an electron. - suborbital levels now exist, also the cloud has 99.99999% of the atom’s volume, but literally none of its actual mass.

Sir James Chadwick:

(1932)

Rutherford’s model did not account for all the mass. Data from Hans Geiger and Ernst Marden showed that the mass of protons in the nucleus was half the atom’s mass. This meant that, at best, protons accounted for half an atom’s overall mass. Thus, some neutral particles must be present somewhere in the nucleus (they knew it wasn’t in the electrons, because mass was concentrated in the nucleus).

Chadwick found neutrons as a by-product of the bombardment of Beryllium with alpha particles.